Alex Hutchinson |

Figuring out how long, how often, and when to train in the mountains remains an art for endurance athletes.

The basic idea is pretty straightforward: you head to the mountains (or crawl into your altitude tent) to force your body to adapt to lower oxygen levels, then you come back to sea level and kick ass in the sweet, oxygen-rich normal air. But nailing the details of altitude training is trickier than it looks, as many would-be mountain athletes have discovered. Get the wrong dose at the wrong time, or do the wrong training while you’re there, and you might end up worse than you started.

A new review in the journal Sports Medicine tries to sum up contemporary approaches to altitude training for endurance athletes. Actually, I should be more specific: it’s a narrative review, which in journal-speak means that the authors have more leeway to tell us what they really think, rather than just summing up the previous literature according to strict rules. That’s significant because the authors—Iñigo Mujika, Avish Sharma, and Trent Stellingwerff—are all notable researchers as well as practitioners working with some of the top athletes in their respective countries (Spain, Australia, and Canada) and around the world. Their goal is to give evidence-based recommendations, but also to draw on their experiences “at the coal face” (as they put it) of current elite practice.

There are a ton of subtleties covered in the 19-page paper (section 4.2.2, for example, covers Augmenting the Hypoxic Stimulus at Terrestrial Altitude with Normobaric Hypoxia or Hypobaric Hypoxia), so I’m going to focus on a few of the more interesting or surprising highlights.

It’s Not (Just) About the Blood

The usual rationale for altitude training is that it ramps up your red blood cell count, increasing the amount of hemoglobin available to ferry oxygen from your lungs to your muscles. But there’s increasing evidence that the body responds to low oxygen levels with other “non-hematological” adaptations that have nothing to do with blood. For example, gene expression related to mitochondria, the aerobic powerhouses in your muscle cells, is ramped up, potentially making your muscles more efficient. The muscles also increase their buffering capacity, which means they’re better equipped to handle the sharp changes in acid-base balance that occur during really intense exercise.

These non-hematological adaptations are far less studied, but there’s some indication that they happen more quickly than the increase in red blood cells. Scientists typically recommend staying at least three to four weeks at altitude to see reliable hemoglobin gains, but the study authors point out that in the real world of elite sport, middle-distance runners often head to altitude during the track season for a two-week “top-up” camp. Athletes and coaches think it works. Perhaps that’s because they’re getting a buffering boost, which would be particularly useful for the high intensity of middle-distance races lasting only a few minutes, rather than the usual blood boost.

Altitude Has Cumulative Benefits

Planning for Tokyo next summer? You probably should have started altitude training several years ago. Your blood cells may have a “hypoxic memory,” enabling them to adapt to altitude more quickly if they’ve been there before. Since the stress of heading to altitude often necessitates a week or so of lighter training once you're up there, being able to adapt quickly allows you to get more out of each stint at altitude. One study that followed Australian swimmers over a four-year period including eight altitude camps found a cumulative hemoglobin increase of about 10 percent—a huge boost compared to the few percent you’d expect from a single camp.

Even within a single year, top athletes use repeated altitude camps to keep building on the previous camp. The review includes training details from several Olympic champions: a swimmer who did 34 camps totaling 120 weeks over eight years; a cross-country skier who spent more than 60 days a year at altitude; a racewalker who spent 45 to 60 days a year.

This heavy use leads the authors to a somewhat provocative suggestion. The conventional wisdom has long been that some people respond to altitude training while others don’t. But many of the studies that find non-responders are one-off studies using non-elite athletes who have never been to altitude before. Apparent non-responders, the review authors argue, “are probably a product of ‘one-off’ camps and/or inadequate planning, periodization, programming, and monitoring of altitude training.”

Timing Your Return Isn’t Everything

How long before your big race should you return from altitude? Every coach has different answers. The most common advice is that you should either race within the first two or three days at sea level, or else wait two or three weeks. This is because you’re balancing a bunch of different positive and negative factors: the gradual decay of your extra red blood cells; the readjustment of your breathing patterns to oxygen-rich air; possible neuromuscular changes because you haven’t been able to train at full speed in the thin air.

All of these factors may have wide individual variation, making it very difficult to pinpoint the right timing. Training data from the Olympic champions was all over the map, with both the skier and swimmer sometimes coming down 7 or 8 days before major championships, right in the middle of the supposedly bad window. Another recent study tracked race performances after an altitude camp and found no obvious pattern, with 60 percent of athletes improving their race times between 3 and 14 days after coming back to sea level. My takeaway: don’t sweat the timing—unless you have a bad experience, in which case you can adjust for next time.

Altitude and Heat Don’t Mix

One of the more tantalizing concepts that has emerged over the past few years is cross-tolerance—the idea that putting yourself through one of kind of stress might help prepare you for dealing with another kind of stress. Most of the interest has focused on the links between heat training and altitude training, which induce some of the same physiological responses. For example, heat-shock proteins are produced in response to both heat and altitude, triggering adaptations that help the body cope with the new stress.

The authors note a couple of examples of elite athletes trying to harness this combination: elite swimmers hitting the sauna three times a week during altitude camps with the hope of boosting plasma volume; Australian racewalkers doing hour-long walks twice a week in a heat chamber during altitude camps. In an article last year, I encountered distance runners who, after returning to Oregon from altitude training in Flagstaff, were hitting the hot tub a few times a week with the hope of prolonging their altitude-induced blood boost.

Despite all the enthusiasm, the evidence for cross-tolerance being useful remains slender at best. In fact, there’s some evidence that if you try to apply two stresses at once, your body will primarily respond to whichever one is worse. So for now, the researchers suggest that if you want to use both heat and altitude training, you should probably do them sequentially rather than both at the same time.

There is, of course, plenty more to consider: keeping your iron levels up to provide the raw material for new hemoglobin formation, possibly eating more to balance an elevated basal metabolism, measuring the oxygen saturation of your blood or even your hemoglobin levels to assess how you’re responding, and so on. In the end, given the complexity of the details and the scarcity of reliable scientific data, anecdotes are probably the best guide we’ve got. So if you’re heading to altitude with the goal of enhancing your performance, ask for help from someone who’s been there before—and got faster.

RECOMMENDED

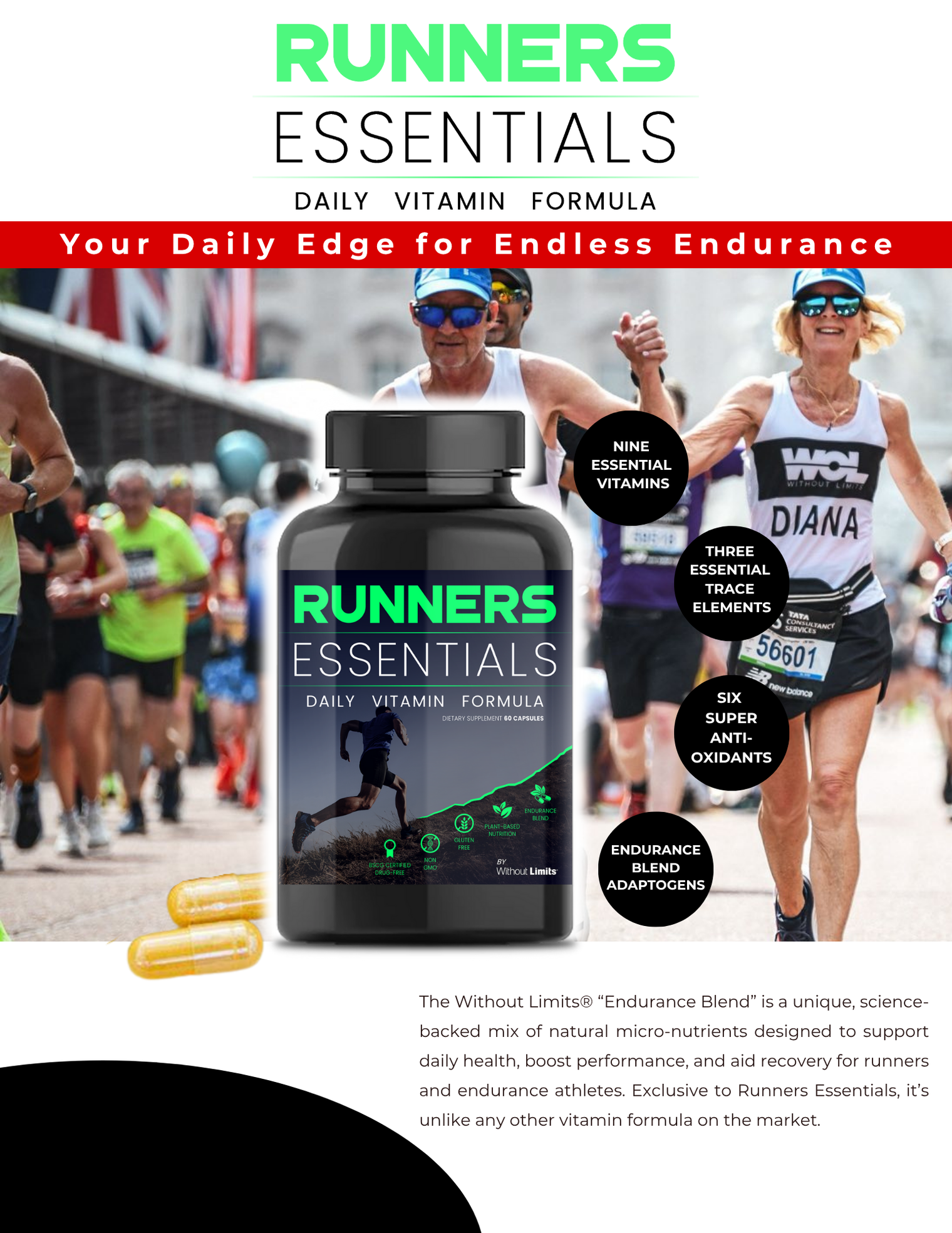

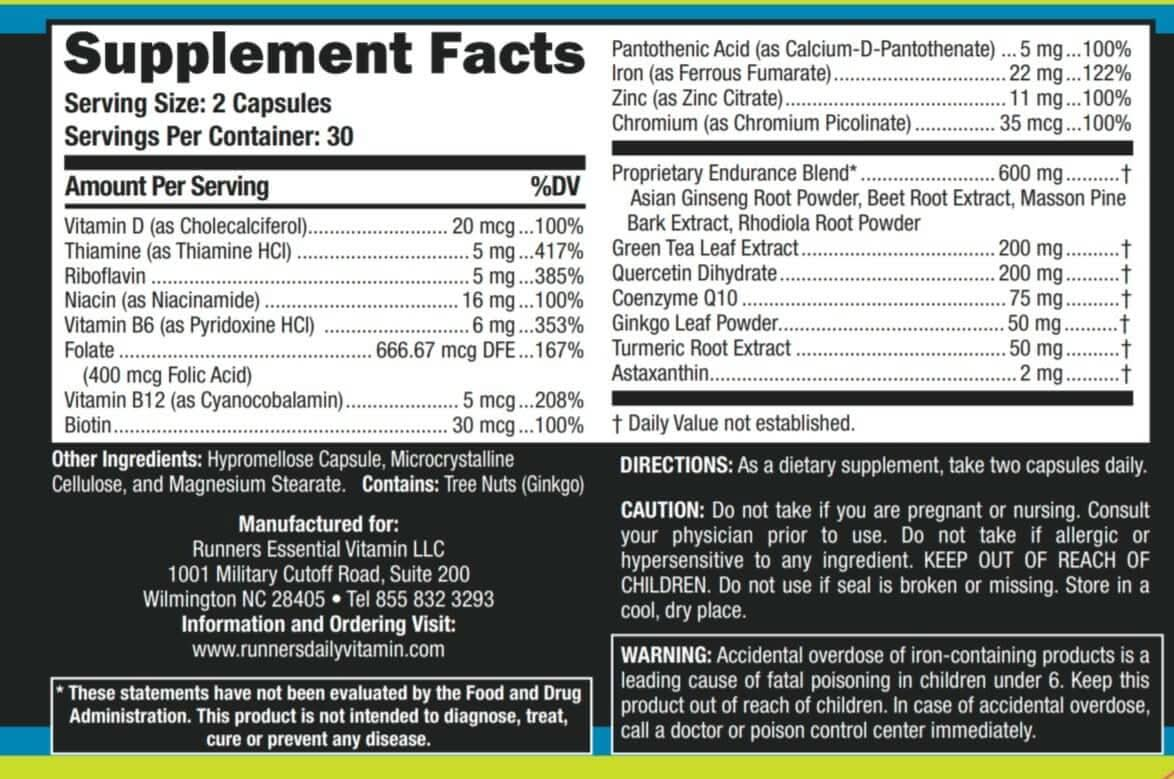

Take your training to the next level with Runners Essentials Daily Vitamin Formula.

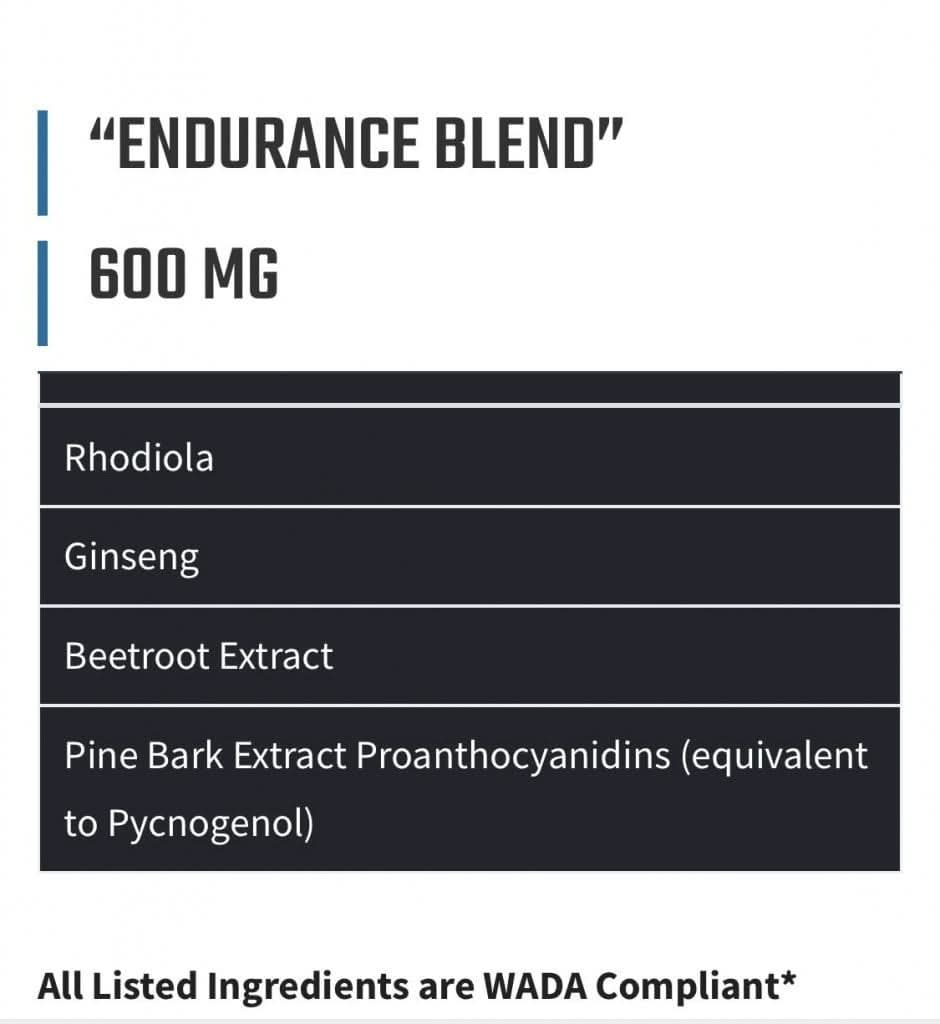

With 4 powerful phytonutrients in a Proprietary "Endurance Blend".

More stories

Herbal Supplements and Benefits for Athletic Performance: Fact or Fiction?

What We Miss by Studying Mostly Men

Set It and Forget It! Up to 35% OFF Single Bottle Price with a Subscription + Free Shipping.

A fusion of science, athletics, and nutrition that maintains an unwavering commitment to quality, content, and purpose. Our daily proprietary formula blends essential vitamins, potent antioxidants, and energy-boosting adaptogens.

Physician, Elite Athlete and Nutritionist formulated and grounded in real science.

- Manufactured in the USA in a GMP and NSF Certified Facility

- Non-GMO, Gluten Free, BSCG Certified Drug Free

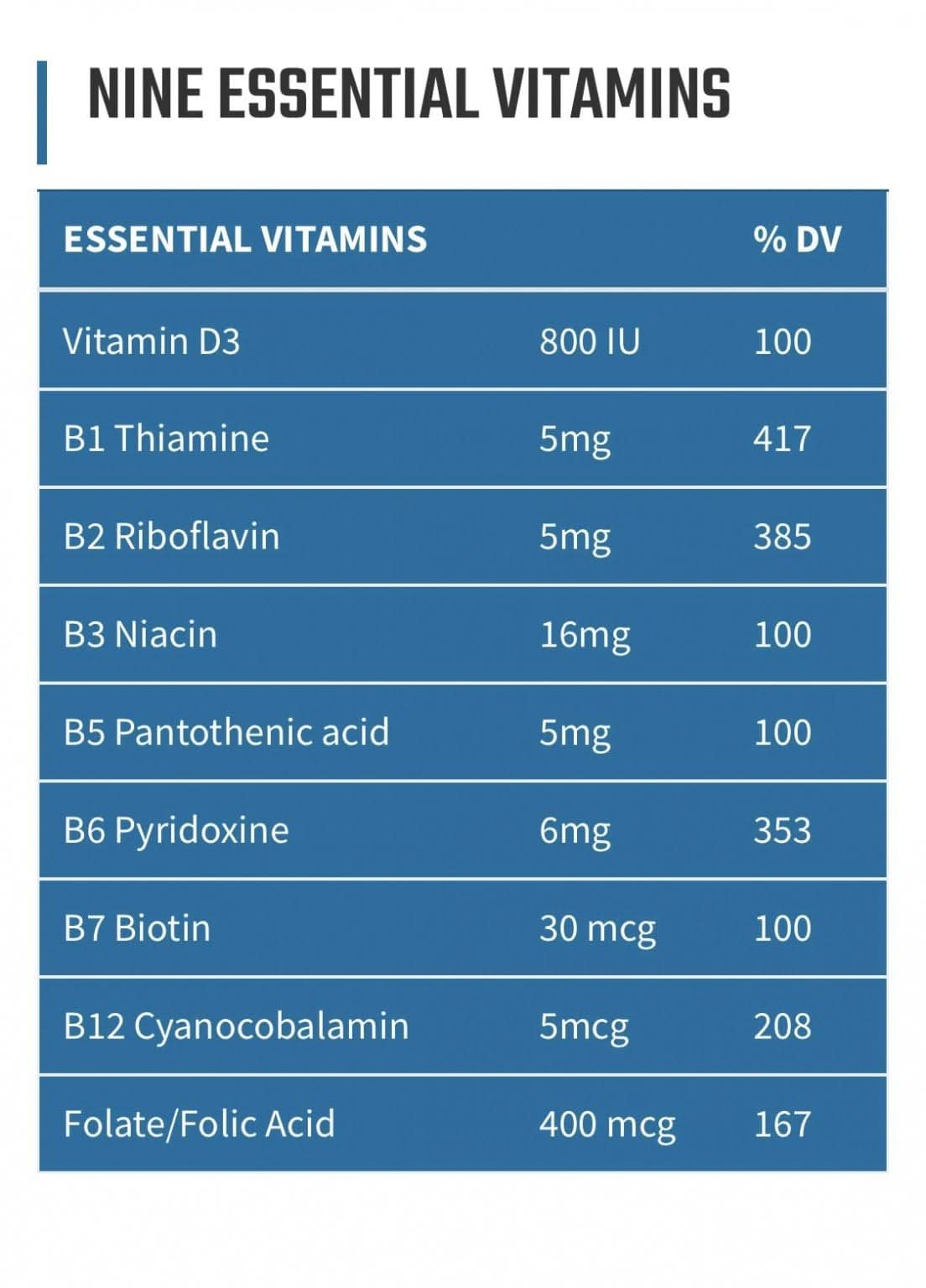

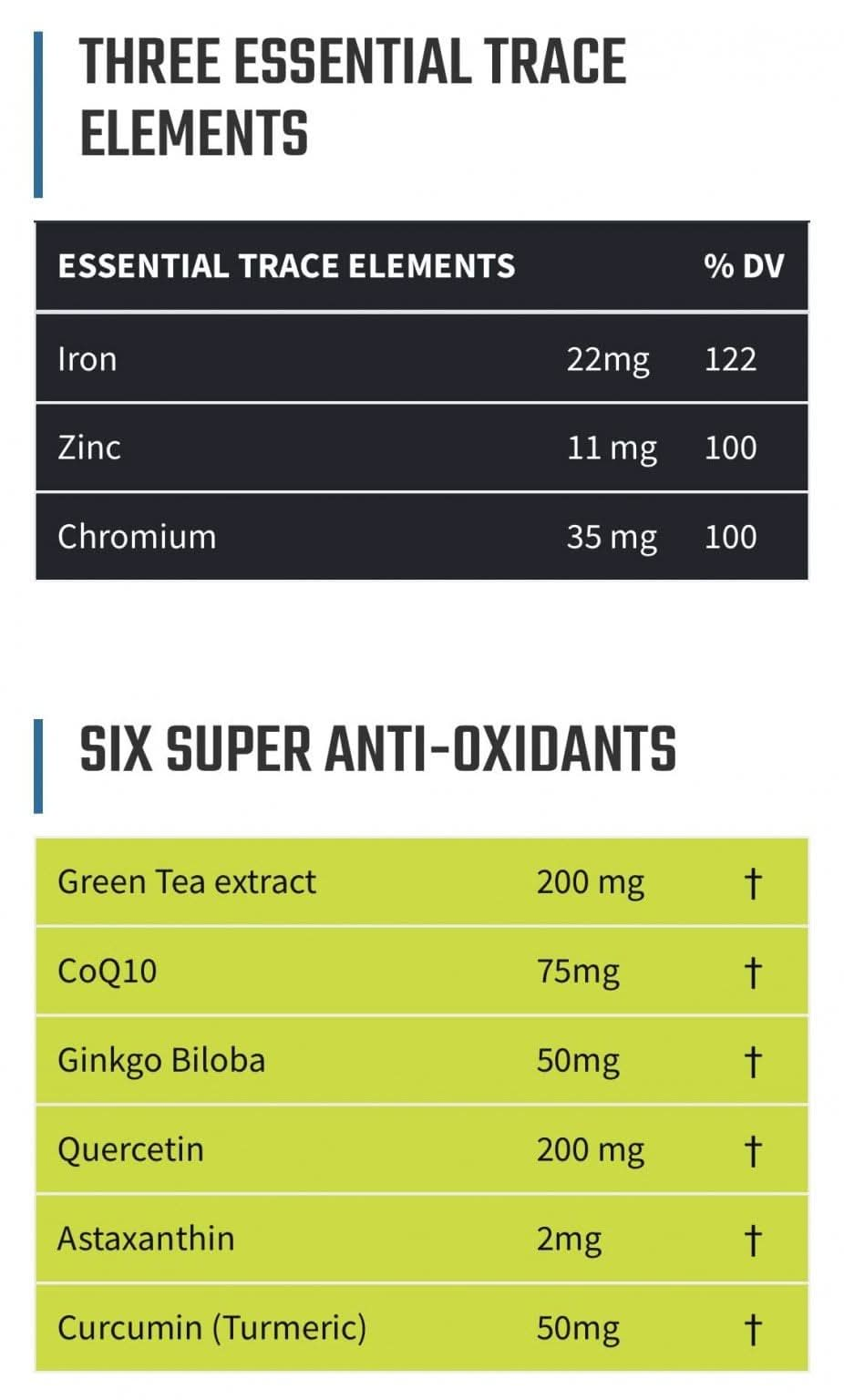

- 22 All-Natural Ingredients with 12 Essential Vitamins and Minerals

- 6 Super Antioxidants and 4 Phytonutrients

- Physician, Elite Athlete and Nutritionist Formulated